Table of Contents

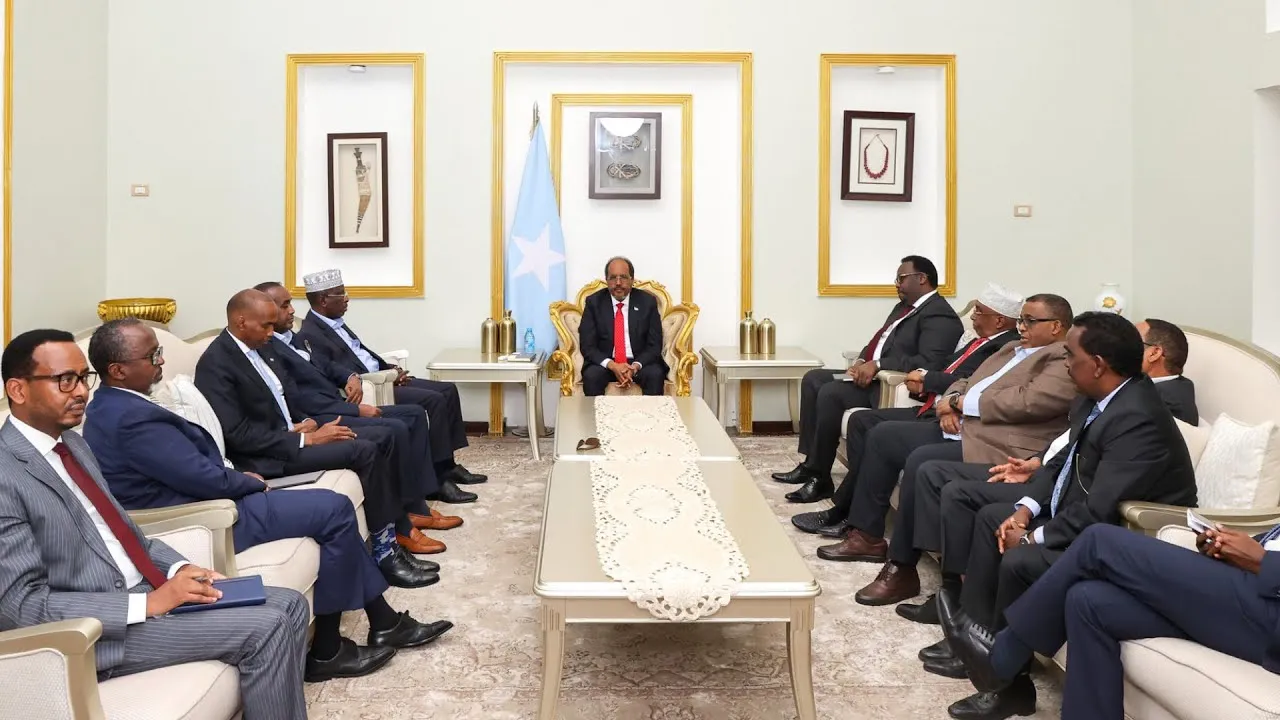

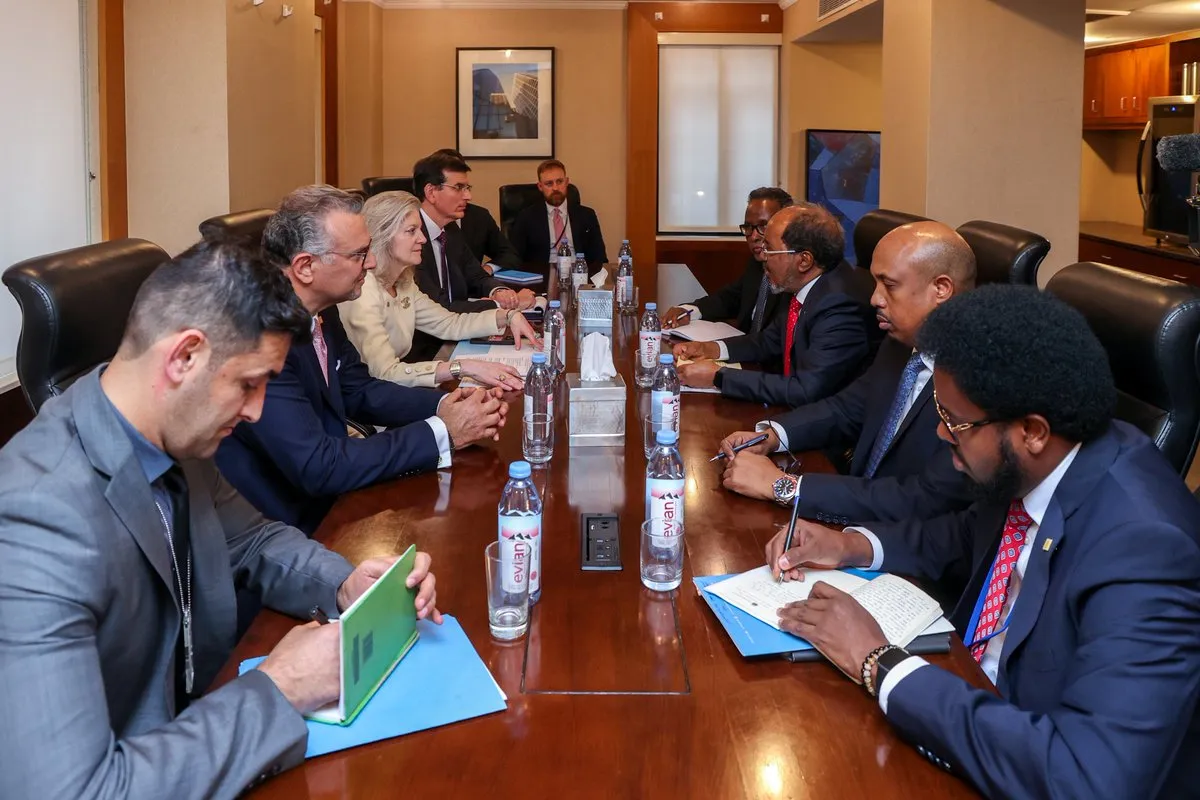

Two parallel gatherings this week, one in Mogadishu and another in Garowe, may mark the beginning of a political agreement in Somalia. President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud is meeting with opposition figures in the capital, while leaders from Puntland and Jubaland convene in Garowe. These talks are meant to resolve critical disputes ahead of the country’s next elections, with three core issues dominating the agenda: constitutional amendments, the choice of electoral model, and the composition of the electoral commission.

The question is whether compromise is possible, or if Somalia will once again stagger toward elections under duress. The stakes are high. President Mohamud has cast himself as a reformer committed to completing Somalia’s long-delayed constitutional process and instituting a “one person, one vote” system. The opposition, unsure of their chances in a new method, has pushed back. At the heart of their contention is how much the President can reshape the political system without their consent, and whether reforms passed by parliament last year were legitimate.

Take the constitutional amendments. The President insists they are both lawful and necessary, claiming a mandate to conclude the draft constitution. Parliament has already ratified a set of changes, and the President argues the only path forward is to persuade the rest of the political class to endorse them. His rivals argue the opposite: that these revisions were rushed through with minimal consensus. In this case, a meaningful resolution may be elusive in these early discussions.

Still, a possible compromise may lie in focusing not on the entire package but on specific clauses that directly affect the coming election. By narrowing the scope of amendments, the government could offer face-saving concessions while retaining momentum. If a political agreement is reached, the revised clauses could be resubmitted to parliament for reendorsement, thus restoring a measure of legitimacy.

The second, and thornier issue is the electoral model. Every President since 2012 has paid lip service to the idea of universal suffrage. Yet elections have always fallen back on the same clan-based, indirect voting system known as the 4.5 formula. Now, President Mohamud’s administration insists this time is different. Despite delays and setbacks, they believe a transition to direct voting is feasible and irreversible.

Reality, however, is less accommodating. The voter registration is incomplete, and swathes of the country remain inaccessible due to insecurity. Federal member states such as Puntland, Jubaland, and Somaliland have shown little appetite for a national voter roll. Some in the opposition share the President’s goal of ending indirect voting but worry that rushed implementation could undermine trust in the process. They fear that the ruling party might tilt the system in its favor, but in principle back the President’s position.

Puntland and Jubaland, meanwhile, have emerged as holdouts. They argue that any deviation from the 2022 model is unacceptable. If they refuse to participate in a direct vote, Somalia faces an awkward predicament: two regions sending MPs via the old model while the rest of the country adopts a new one. Such a hybrid system may be administratively complex but politically necessary if consensus proves elusive. Alternatively, there may be a consensus to extend the current Parliamentary and Presidential until the new election mode issue is resolved.

The third issue, reforming the electoral commission, may be the least controversial and therefore the easiest to resolve. The current disagreement centers on the composition and perceived neutrality of commission members. Here, President Mohamud is likely to be more flexible. If progress is made on constitutional and electoral questions, agreeing on a mutually acceptable commission could serve as a final confidence-building measure.

This would require more than symbolic gestures. The government and opposition must jointly vet nominees, define operating procedures, and set rules that preclude interference. In a system long plagued by accusations of manipulation, even small procedural guarantees could bolster the commission’s credibility and the wider electoral process.

Ultimately, the challenge is not just legal or logistical, but deeply political. Trust is in short supply. Every action is scrutinized for ulterior motives, every concession weighed for signs of weakness. Yet Somalia cannot afford another election cycle marred by suspicion and violence. The coming weeks, along with the ongoing dialogue between the President, the opposition, and regional leaders, offer an opportunity to set a different tone —one that prioritizes negotiation over confrontation.

The opposition must decide whether to remain a spoiler or participate constructively in shaping Somalia’s political future. And, President Mohamud must be willing to listen and moderate to secure broader legitimacy for his reform. The risk of stalemate is real, but so too is the potential for incremental progress in Mogadishu and Garowe meetings, allowing all parties to discuss the substance of the three core political disagreements and agree on at least a partial roadmap.